Image 1 of 1

Image 1 of 1

Free Online Talk · Globalization and the Emergence of Living Deads along the African Silk Road with Program Director for IHP Death and Dying, Dilpreet Singh Basanti

Monday, November 10, 2025

7pm ET (NYC time)

Free! RSVP with email at checkout

PLEASE NOTE: Video playback of free events is only available to Patreon members. Become a Member HERE.

Ticketholders: A Zoom invite is sent out two hours before the event to the email used at checkout. Please check your spam folder and if not received, email hello@morbidanatomy.org.

When do ghosts come into being? This talk looks how living deads and ancestors may emerge to transform societies in globalization. Cross-cultural studies demonstrate that death is not an immutable boundary but one that weakens and strengthens alongside major social transformations. Archaeology is a great way to look at death across cultures in long timelines that reveal shifting histories of change. Modern death in the Global North is a product of a long history of individualization and growing separation of the living from death spaces beginning in medieval times. In consequence, death today is characterized by simplified planned burials, hyper-individualized death rites, “death denial”, the sequestering of death and dying to clinical spaces, and an understanding of death marks the end of a person. Social evolutionary thought has led people to believe that cultures where death is not very strong - such as where ancestors and ghosts are stronger - are conversely "non-modern." The present dead, as ancestors, ghosts, or the still-there-in-some-way, are often considered ritual or religious aspects of the past still surviving in a world with little place for them.

Yet this is not what we see in history. Social processes like globalization or urbanism change the reality of death and cross-cultural archaeology provides unexpected results. In northern Ethiopia, the kingdom of Aksum (80 BCE — 825 CE) became a major global power along the sea routes of the Silk Road - eventually listed as one of the four greatest powers of its time alongside their trading partners of Rome, China, and Persia. Aksum's main markets were in India and Sri Lanka, where the people traveled frequently. During this era of globalization, Aksumites began to build giant funerary monuments imbued with ritual power that amplified new rites of returning to the dead and processing their remains. The symbolism of death in Aksum is a symbolism of houses, gateways, and loved ones they would never abandon. Aksumites began living "virtually" with ideas of "local" and "foreign" and didn't allow foreign goods in their graves despite consuming them everywhere else. The ancestor or the still-there-in-some-way for these people were not relics of the past, but new beings that emerged to manage their cosmopolitanism, inequality, and to keep families together through sweeping histories of change.

This talk will explore this history and look at the ways that the boundary of death weakened alongside the globalization of the African Silk Road.

Dil Singh Basanti is an anthropological archaeologist that explores the differing beliefs, experiences, and social life of death across cultures. Dil is the director of IHP Death and Dying study abroad program at the School for International Training that explored cross-cultural deathways in New York, Accra, Oaxaca, and Bali. Dil also directs the Aksum Bones Project, which reconstructs the changing history of death along Silk Road Ethiopia through forensic archaeology. Dil’s research has been sponsored by the National Science Foundation, Wenner-Gren Anthropological Foundation, US Fulbright Program, and National Geographic, among others. Dil has over 15 years of archaeological field experience excavating across five continents.

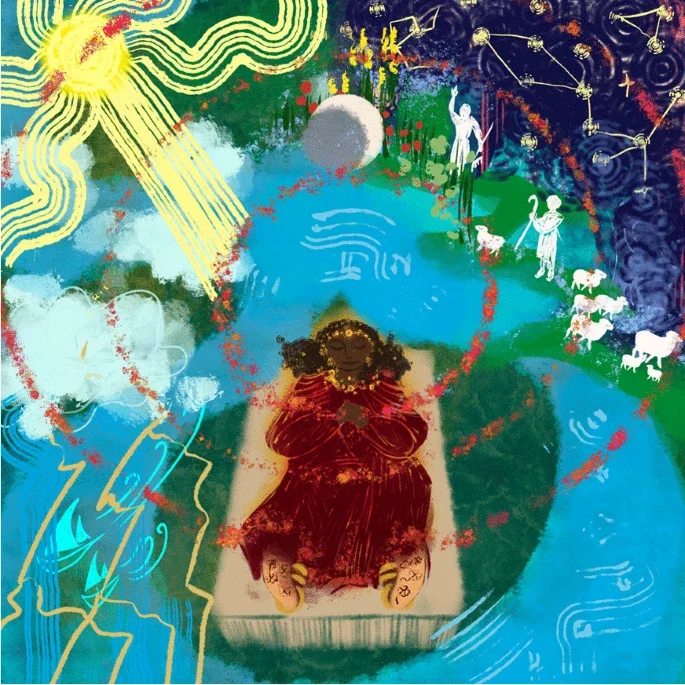

Memory of a young woman buried. Original artwork by Naomi Mekonen

Monday, November 10, 2025

7pm ET (NYC time)

Free! RSVP with email at checkout

PLEASE NOTE: Video playback of free events is only available to Patreon members. Become a Member HERE.

Ticketholders: A Zoom invite is sent out two hours before the event to the email used at checkout. Please check your spam folder and if not received, email hello@morbidanatomy.org.

When do ghosts come into being? This talk looks how living deads and ancestors may emerge to transform societies in globalization. Cross-cultural studies demonstrate that death is not an immutable boundary but one that weakens and strengthens alongside major social transformations. Archaeology is a great way to look at death across cultures in long timelines that reveal shifting histories of change. Modern death in the Global North is a product of a long history of individualization and growing separation of the living from death spaces beginning in medieval times. In consequence, death today is characterized by simplified planned burials, hyper-individualized death rites, “death denial”, the sequestering of death and dying to clinical spaces, and an understanding of death marks the end of a person. Social evolutionary thought has led people to believe that cultures where death is not very strong - such as where ancestors and ghosts are stronger - are conversely "non-modern." The present dead, as ancestors, ghosts, or the still-there-in-some-way, are often considered ritual or religious aspects of the past still surviving in a world with little place for them.

Yet this is not what we see in history. Social processes like globalization or urbanism change the reality of death and cross-cultural archaeology provides unexpected results. In northern Ethiopia, the kingdom of Aksum (80 BCE — 825 CE) became a major global power along the sea routes of the Silk Road - eventually listed as one of the four greatest powers of its time alongside their trading partners of Rome, China, and Persia. Aksum's main markets were in India and Sri Lanka, where the people traveled frequently. During this era of globalization, Aksumites began to build giant funerary monuments imbued with ritual power that amplified new rites of returning to the dead and processing their remains. The symbolism of death in Aksum is a symbolism of houses, gateways, and loved ones they would never abandon. Aksumites began living "virtually" with ideas of "local" and "foreign" and didn't allow foreign goods in their graves despite consuming them everywhere else. The ancestor or the still-there-in-some-way for these people were not relics of the past, but new beings that emerged to manage their cosmopolitanism, inequality, and to keep families together through sweeping histories of change.

This talk will explore this history and look at the ways that the boundary of death weakened alongside the globalization of the African Silk Road.

Dil Singh Basanti is an anthropological archaeologist that explores the differing beliefs, experiences, and social life of death across cultures. Dil is the director of IHP Death and Dying study abroad program at the School for International Training that explored cross-cultural deathways in New York, Accra, Oaxaca, and Bali. Dil also directs the Aksum Bones Project, which reconstructs the changing history of death along Silk Road Ethiopia through forensic archaeology. Dil’s research has been sponsored by the National Science Foundation, Wenner-Gren Anthropological Foundation, US Fulbright Program, and National Geographic, among others. Dil has over 15 years of archaeological field experience excavating across five continents.

Memory of a young woman buried. Original artwork by Naomi Mekonen